19 May 2023

The impacts of climate change are increasingly felt around the globe, impacting human health, livelihoods, businesses, and critical infrastructure, including transport, water, sanitation, and energy systems. The challenges are even more significant in cities due to increasing urbanisation and unsustainable planning. And although we have invested effort and resources in creating flood-resilient environments, we are far from resilient if we look at the overall climate risk.

How can we expand our thinking on climate risk and become more aware of the potential consequences?

Changes in global climate challenge the resilience of our cities and infrastructure worldwide. While enhancing mitigating action to reduce carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions is still critically needed to meet the Paris Agreement and Net Zero goals, at the same time, based on the latest United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Synthesis Report, it is essential to take more ambitious action to adapt to the now unavoidable extreme, compound, and multi-hazard events that can cause significant and long-lasting impacts. Although the focus is currently on extreme hydrological and flooding events affecting billions of people worldwide, we also need to increase our understanding of other climate stressors (for example, extreme heat, wildfire, and drought) or interrelated events that have started challenging our societies.

We live in a time of constant change and record-breaking. Last year in the UK, we experienced record-breaking heat (2022 was the warmest year on record for every nation of the UK) and the coldest day in 12 years. We also had record-breaking winds from Storm Eunice, causing structural damage, disruption in transport and utilities and death and injuries. In Europe, we experienced the worst drought in the past 500 years, record-breaking heatwaves, and deadly wildfires. Climate change is making extreme events more likely, and more intense and single climate hazard occurrences are seen to give rise to other hazard types; more significant air pollution events, droughts, wildfires, and flash flooding are some examples of the aftermath impacting the built and natural environment, infrastructure, economy, and human health. Are we doing enough to create better environments?

We also live in an interconnected world with interlinked risks; an urban environment will likely experience more than one challenge at a time. At the same time, climate impacts in one location will likely spread to other areas through value chains, distribution networks and systems. These effects often need to be addressed holistically through climate risk assessment approaches and systems thinking. A business-as-usual reactive practice focused on a single type of hazard does not provide the required level of resilience to deal with the dimensions of climate risk, especially in the case of extreme or interrelated climate events.

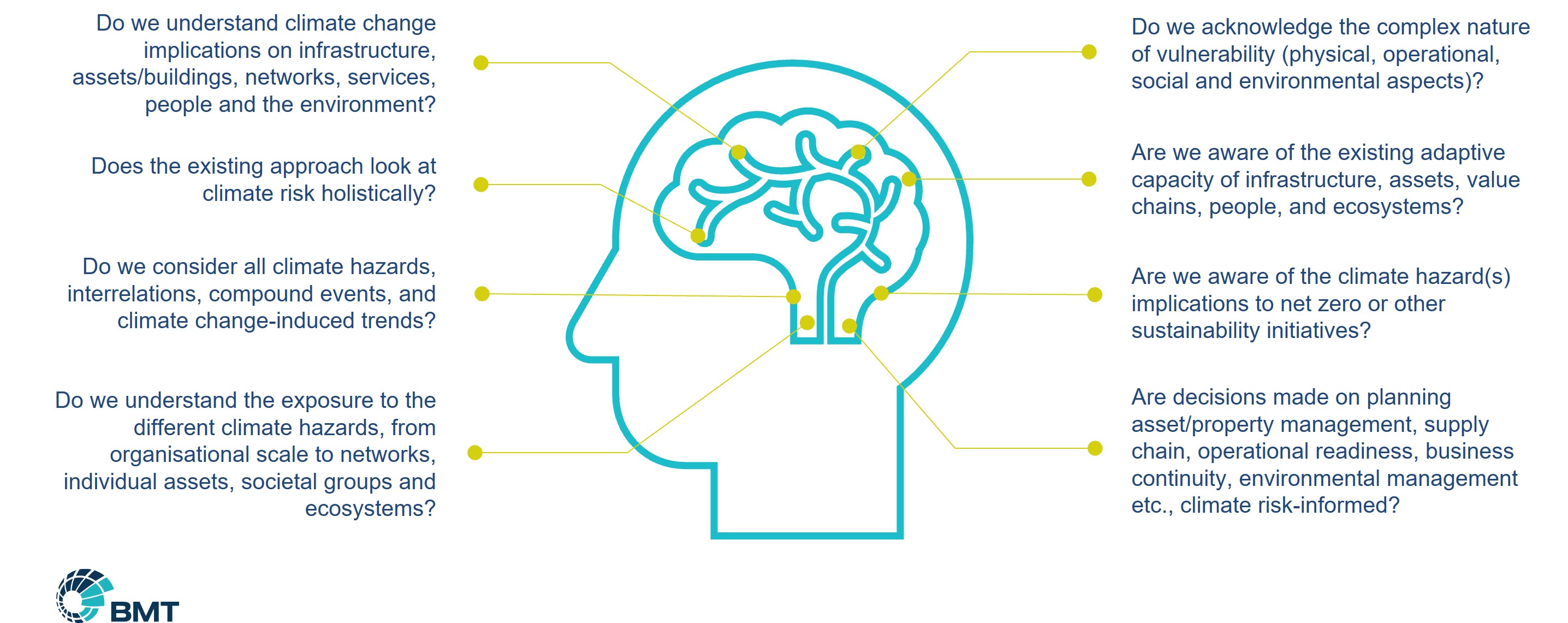

Due to the inherent complexity of climate science and related risks, it is essential to step back and look at what is necessary for the overall risk conceptualisation and risk mitigation process. And there are many aspects to consider, as depicted in the below figure; from how comprehensive our understanding of the risk determinants is to how we make decisions on planning and operational matters.

What to consider as part of the risk conceptualisation and mitigation process.

Planning for a climate-resilient future implies creating risk-aware and forward-looking solutions and a governance model able to respond to evolving types of risk. The new normal requires employing a holistic risk analysis approach considering different types of climate hazards, from slow onset processes to extreme weather events and their interaction and assessing economic and non-economic losses and damages. Developing scenarios to plan for a range of possible climate futures can help make robust decisions; however, the identification process for climate hazard types and action should look at impact chains to understand risks and cause-effect relationships and the scale of impacts on infrastructure, assets, settlements, value chain and networks, people, and ecosystems. Design and planning aspects should also become more forward-looking and not based on present or historical thresholds and specifications.

Acknowledging relationships is essential in developing responses and solutions to climate risk. Often, the way we plan or respond to climate risk is highly compartmentalised or addresses only high-likelihood outcomes. Even in the case of response or recovery plans, we tend to adopt approaches that only address a specific aspect. This practice will probably not meet the demands of tomorrow as it misses to address that the change will likely impact the whole system and not just one part of it or that even low-likelihood events can have very large adverse impacts.

Also, how we deal with climate risk affects how we address equity, equality, and inclusion aspects, reducing or not existing social vulnerabilities. Losses are distributed disproportionately, with the most vulnerable societal groups facing the most significant challenge, especially considering current energy prices and the need for heating or cooling. Therefore, climate resilience planning should acknowledge both physical and social vulnerabilities.

In the face of constant change, have we built the right foundations to develop our adaptability further? Are we aware of the existing capacity of urban or infrastructure systems, businesses, and communities to adapt? Climate risk analysis should incorporate aspects of existing adaptability, looking at the ability to deal with short-term climate-related threats, adjust to potential damage, and act to become better equipped to cope with future change. Given that we are heading into unchartered waters, looking at best practices to overcome commonly encountered challenges and learning from past experiences can be very helpful. However, we need to acknowledge that adaptation options that are feasible and effective today are likely to become less effective in the future.

An essential element, often overlooked, is how people perceive risk and how perceptions can drive action and influence behaviours before, during or after a hazardous event. In regions prone to flooding, there is usually a mechanism to raise awareness about the risk, minimise the impact and prepare for an effective emergency response when the event occurs. At a council level, this may include, amongst others, having flood protection, flood risk management and preparedness plan, while at a personal level, knowing what to do before, during and after a flood. Is there a similar level of awareness for heatwaves, cold spells, storms, droughts, or even wildfires? Even though in the UK we already experience record-breaking heatwaves and an increase in temperature compared to pre-industrial levels, in the past years, over half a million new homes have been built that are not resilient to high temperatures.

A climate risk-aware culture is fundamental to developing responsible behaviours and finding ways to future-proof our cities, businesses, and societies. Building the required level of awareness requires having appropriate knowledge about climate hazards, how they can interact or cascade, and their implications. Undoubtedly, transformation is needed in the current thinking practice in response to climate hazard occurrences or their effects. Shaping our thinking to become more risk-aware can shift how we anticipate risk allowing more responsible behaviour during planning, response, or even recovery after the event.

What decisions would you make differently if you had more clarity on climate risk and resilience? Get in touch to discuss how we can help you better understand climate risk-related implications!

Asimina is a climate risk and resilience and environmental specialist with broad experience in consulting and management roles, supporting organisations to analyse climate hazards and assess related risks, build adaptive capacity, and become more sustainable. She has experience developing new services in the environmental domain, building capabilities, and leading complex projects and high-value strategic commercial opportunities.

She is a Doctoral Researcher at Cranfield University working on analysing the risk of climate hazards to airport systems. She holds a BSc in earth sciences, an MSc in environmental planning and infrastructure design, and an MSc by Research in airport environmental strategy assessment and water management efficiency. She is the Editor in Chief of the European Geosciences Union Natural Hazards Division blog.

Noel Tomlinson - Maritime Design

Noel Tomlinson shares with SBI valuable insights on how BMT's innovative solution can help vessel operators overcome challenges and ensure a sustainable future for offshore wind operations.

Jaret Fattori

Jaret Fattori's article in Port Strategy discusses how ports are adapting to climate change and IFRS S-2 regulations. Emphasising the shift towards sustainability through digital integration, decarbonisation, and innovative fuel alternatives, he explores the significant role of collaboration in advancing port sustainability and innovation.

Ian McRobbie

Ian McRobbie, our Programme Manager for Ports and Maritime Infrastructure, was interviewed by Port & Harbors to discuss how infrastructure companies are collaborating with ports to enhance port infrastructure and operations.

Jaret Fattori

The regulatory landscape in Canada is evolving rapidly, reflecting a growing awareness of the need for more sustainable practices and responsible business conduct.