19 July 2023

The summer is in full swing, and the UK has already experienced the first sustained period of hot weather. In 2022, the thermometer reached unprecedented temperature levels for July in the United Kingdom (UK) (40.3°C was recorded at Coningsby in Lincolnshire on 19 July 2022), setting a new high-temperature record. How hot will it be this summer? The Met Office annual global temperature forecast for 2023 suggests that this year will be one of the Earth’s hottest years.

Heatwaves are similarly breaking records worldwide, and, considering the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6), the frequency and intensity of hot extremes will continue to increase. Although the UK currently experiences heatwaves with a lesser frequency and intensity compared to other European countries, the projections suggest that within the following decades, hotter and drier summers are likely to become more common, and the chance of seeing more than 40°C temperature occurrences in the UK seems more and more likely. Considering that El Nino will likely create conditions hard to predict, there is an urgency to take action to reduce societal risks from extreme weather occurrences such as heat.

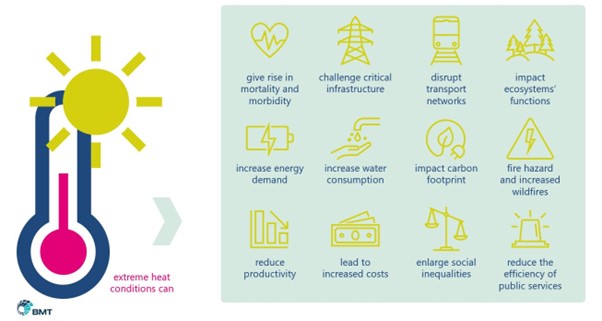

Extreme heat tends to escape our attention as a hazard due to the ‘silent’ effects, or the difficulty in quantifying its impact due to the lack of data. Yet, the World Health Organisation considers heatwaves one of the most dangerous natural hazards to human health. Without a doubt, extreme heat has the potential to give rise to mortality and morbidity, challenge critical infrastructure, networks, social services, and business resilience, and enlarge social inequalities. The impact of extreme heat in areas with dense concentrations of buildings and paved surfaces can be even more significant, as these structures absorb and amplify heat, especially with limited green space. The urban environment tends to be warmer than the surrounding suburbs or rural areas, especially at night, an effect called Urban Heat Island.

Some of the implications of extreme heat conditions

The impacts of heat extremes can be catastrophic, as historically shown by many heat-related deaths; from 1998-2017, more than 166,000 people died due to heatwaves, including more than 70,000 who died during the 2003 heatwave in Europe. Last year’s heatwave caused over 20,000 heat-related deaths, with the UK alone recording the largest number of excess deaths between June and August, according to the Office for National Statistics and UK Health Security Agency. Undoubtedly, heatwave conditions can lead to increased heat-related mortality and hospitalisations. This can be exacerbated by poor air quality conditions in urban areas, wildfires, and blackout events, all common during extreme heat events.

Extreme heat puts pressure on critical infrastructure and essential services such as transport, utilities, and public services like emergency response and health services. Heatwaves increase the demand for cooling, with increased energy costs and the risk of power failures due to surges in demand, which can compromise transport, communication, water, and fuel supply. Typically, the number of blackout events increases during the summer when electricity demand is at its peak. Also, within aviation, rail and road transportation, extreme heat can lead to damage to transport infrastructure (for example, damage to the overhead electric wires in rail or damage to pavements and airport runways) and service disruption (for example, introducing speed restriction, route cancellation and delays). These events can also impact supply chain and distribution networks, challenging business resilience and creating operational challenges as people cannot get to work.

Heatwaves also impact labour productivity, especially in construction, agriculture, and outdoor services industries. Production interruptions may occur during heatwaves because of policy enforcement or health and safety considerations, affecting workers’ income and the global economy due to reduced output. These effects will likely be more significant to vulnerable societal groups, increasing existing inequalities or leading to migration.

Although the effects of heat are likely to be exacerbated in urban environments, non-urban or rural communities can also be affected by hot conditions. Extreme heat can challenge crop production and livestock mortality or impact ecosystems’ function and vulnerability. There is high confidence that heat extremes have led to the loss of hundreds of local species, with mass mortality events recorded on land and in the ocean (IPCC AR6).

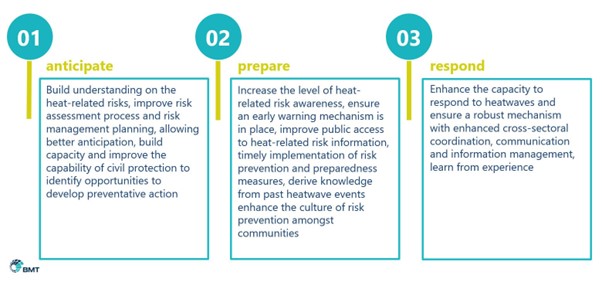

The exact nature of risks emerging from extreme heat conditions is not typically easy to identify using traditional risk analysis and management approaches if we fail to consider the interconnectivity and interaction of systems. Also, it is essential to consider the existing levels of risk perception and elements that reflect actions towards building adaptive and recovery capacity and integrate them into the analysis. With heat waves projected to increase in frequency, intensity, and duration, cities must develop an approach to reduce heat-related impacts. To develop such an approach, we should invest in proactive action, building anticipation, enhancing preparedness levels, and ensuring an efficient response mechanism.

Elements of proactive action to reduce heat-related impacts in cities

One of the most critical elements in proactive action is understanding how a heatwave might impact our cities, from infrastructure/assets and operations/services to communities and ecosystems. Organisations need to comprehensively understand the heat-related risk over the short and long term and the existing vulnerabilities (physical and social) to plan for resilience. Many factors influence related risks, and a balance is needed to ensure that climate change mitigation and adaptation actions are well aligned. For example, if not naturally ventilated, an energy-efficient and well-insulated building can become uninhabitable if there is a power outage during a heatwave. As part of this process, it is critical to identify hotspots in terms of areas that are more exposed to heat due to

An analysis of the vulnerability and existing levels of adaptability considering the evolution of heat hazards due to climate change influence will identify areas to focus on to build further resilience.

When designing or retrofitting, adopt more stringent specifications, building codes and safety standards aligned with the requirements of the future and consider adaptive opportunities that can enable infrastructure, assets, or buildings to increase resilience to heat. For example, consider passive cooling measures such as cool roofs, cool pavements, or improved building design to reduce heat retention (for example, green roofs, shading and natural ventilation), ensure that existing cooling capacity can address future needs, or the specifications of building and infrastructure material are fit for purpose. In newer construction zones, an option to explore is district cooling.

Approaches like urban greening, restoration of wetlands and ecosystems, and green and blue infrastructure are examples of approaches used to reduce the impact of extreme heat in the urban environment. Ecosystem-based adaptation approaches are generally effective in reducing urban heat while supporting carbon uptake and storage or, in some instances, flood risk mitigation.

Having guidelines and a roadmap helps organise activities considering the dynamic nature and interconnectedness of the urban environment. Successfully developing a plan requires cross-departmental collaboration to include emergency management, health and social services, city planning, meteorological services, infrastructure operators, and transport authorities, to name a few. The development of the heatwave plan needs to consider different climate scenarios and the scale of likely impact and related interdependencies and should be updated regularly.

Many countries have introduced heatwave early warning systems in response to the mortality and morbidity of recent heatwave events. Early warning systems are designed to reduce the health consequences of heatwaves that can be avoided; they involve forecasting the heatwave effect, predicting possible health outcomes, and triggering timely notification of prevention measures to vulnerable populations. For example, the UK Health Security Agency has recently updated the Adverse Weather Alerting service for England to include heat-health alerts, providing advanced warnings to healthcare professionals and the public to prepare. Another practice that cities have started applying is categorising and naming heatwaves based on their effect on human health, a practice followed in the case of storms.

Many councils conduct public awareness campaigns to increase knowledge of heat-related risks and heat risk reduction strategies; they provide information on what to do before, during and after a heatwave.

In many cases, urban planning policies are based on historical data, limiting the ability to efficiently address the dynamic nature of climatic change and relevant implications. Having informed policies in place is crucial as it allows decision-makers to proactively act to identify interventions to facilitate effective adaptation. This requires using current scientific knowledge of climate change and a comprehensive analysis of the implications of extreme heat.

Contact us to discuss how we can help you better understand heatwave-related implications.

Asimina is a climate risk and resilience and environmental specialist with broad experience in consulting and management roles, supporting organisations to analyse climate hazards and assess related risks, build adaptive capacity, and become more sustainable. She has experience developing new services in the environmental domain, building capabilities, and leading complex projects and high-value strategic commercial opportunities.

She is a Doctoral Researcher at Cranfield University working on analysing the risk of climate hazards to airport systems. She holds a BSc in earth sciences, an MSc in environmental planning and infrastructure design, and an MSc by Research in airport environmental strategy assessment and water management efficiency. She is the Editor in Chief of the European Geosciences Union Natural Hazards Division blog.

N/A

The DCN spoke to our climate change risk, resilience and adaptation expert about preparing for the impacts of a changing climate.

N/A

With the UK and beyond facing unprecedented consequences from rising water levels and climate amelioration, BMT are helping our clients in their need for flood alleviation, prediction, mapping and mitigation. James While talks about 5 ways we can assist our clients.

Ian McRobbie

In a Port Strategy feature, Ian McRobbie highlights the merits of optimising bulk transshipment through ‘Climate-Smart’ simulation technology, drawing on extensive project experience

Jaret Fattori

Jaret Fattori's article in Port Strategy discusses how ports are adapting to climate change and IFRS S-2 regulations. Emphasising the shift towards sustainability through digital integration, decarbonisation, and innovative fuel alternatives, he explores the significant role of collaboration in advancing port sustainability and innovation.